Best Practices: file names and folder structures

The world according to GARP…

The world according to GARP…

In our data management courses we always discuss the way participants document and organise their data files. One of the questions is how to keep track of your data. Will you be able to find a specific dataset in due time? Will others be able to find and understand it? This is crucial if you or anyone else wants to use your data later on. One of the first things to do is to name your files and structure your folders in a consistent way. It is even better if you and your colleagues use the same standard.

Dr. Liesbeth de Lange has successfully developed the GARP standard in her group at the LACDR institute (Faculty of Science). Rutger de Jong asked her how this standard came into being and how it was adopted. You can read the interview below. Inspired? Why not organise a ‘data organisation day’ at your institute, another nice idea born at the LACDR.

Dr. Liesbeth de Lange has successfully developed the GARP standard in her group at the LACDR institute (Faculty of Science). Rutger de Jong asked her how this standard came into being and how it was adopted. You can read the interview below. Inspired? Why not organise a ‘data organisation day’ at your institute, another nice idea born at the LACDR.

Data structurally sound

If you want to make your documents findable, you have to think about the file name and folder structure. As a PhD-student Liesbeth de Lange of the LACDR developed a system of conventions she still profits from today. These conventions are now a central part of her departments ‘good academic research practice’.

GARP is a word Liesbeth de Lange, associate professor of pharmacology, regularly drops in conversation. It is an acronym of Good Academic Research Practice (GARP). GARP ensures all data produced by research can still be used in the future. “You can use the same research data to answer multiple questions if you design the experiment correctly. Later on, it may even answer questions you did not think of at the time.”

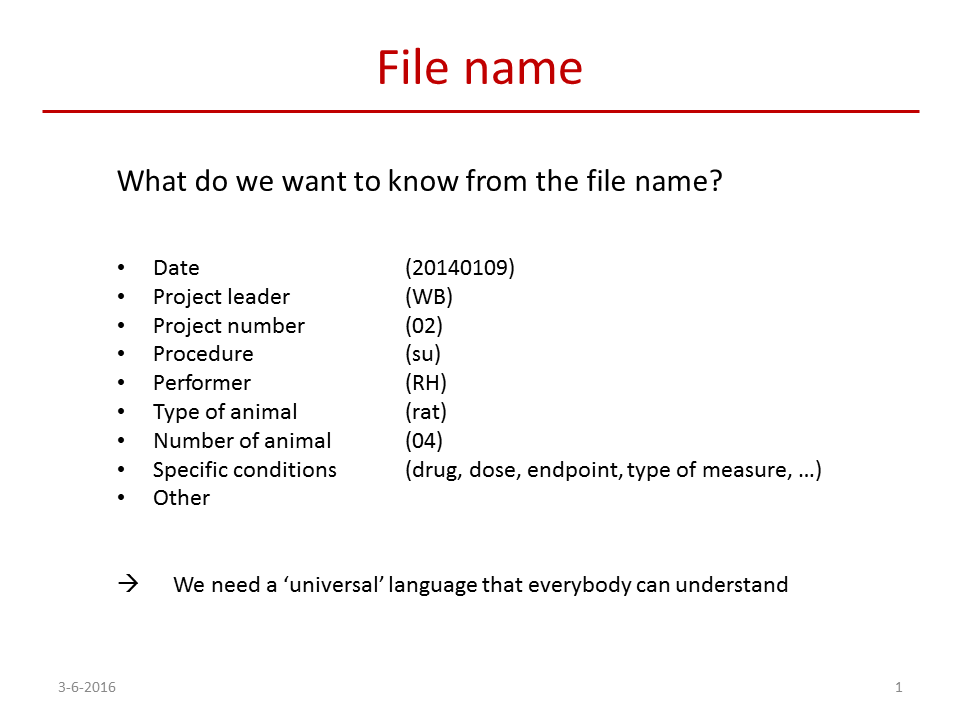

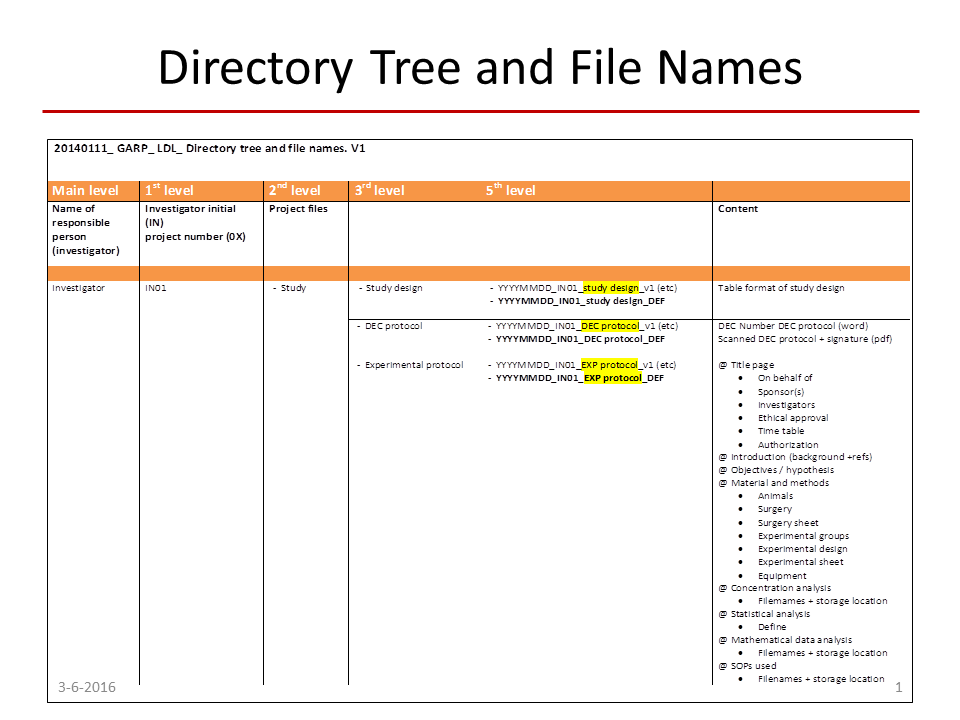

Good data storage and management is an important aspect of GARP. Good data storage means that every file name has to be unique, describes its contents concisely and has to contain the date and person responsible for the experiment. That way we can easily see that the concentration profile of a medicine was measured in a rat and in a specific location in its body. De Lange: “The effect of a medicine is correlated to its concentration at the site of action. That concentration can strongly vary between the heart and the brain, partly because there is a blood-brain-barrier that prevents the medicine from reaching the brain. Old data sometimes misses such information on the location of the measurement, so in that case it takes a lot of time to find out what was actually measured.” To make the folder and file parameter and storage location as uniform as possible, the group compiled a thesaurus, a list with defined abbreviations that the researchers may use in their file names.

Good data storage and management is an important aspect of GARP. Good data storage means that every file name has to be unique, describes its contents concisely and has to contain the date and person responsible for the experiment. That way we can easily see that the concentration profile of a medicine was measured in a rat and in a specific location in its body. De Lange: “The effect of a medicine is correlated to its concentration at the site of action. That concentration can strongly vary between the heart and the brain, partly because there is a blood-brain-barrier that prevents the medicine from reaching the brain. Old data sometimes misses such information on the location of the measurement, so in that case it takes a lot of time to find out what was actually measured.” To make the folder and file parameter and storage location as uniform as possible, the group compiled a thesaurus, a list with defined abbreviations that the researchers may use in their file names.

Since she started working as a PhD student in 1990 at Leiden University, De Lange has been able to reach back around twenty times to old internal data for re-use. This was partially possible because of the structure GARP brought. By re-using data she not only saved costs, but she also prevented additional animal tests. To help other researchers get the most out of their data, she likes to share the success story of GARP.

Since she started working as a PhD student in 1990 at Leiden University, De Lange has been able to reach back around twenty times to old internal data for re-use. This was partially possible because of the structure GARP brought. By re-using data she not only saved costs, but she also prevented additional animal tests. To help other researchers get the most out of their data, she likes to share the success story of GARP.

When and why did GARP evolve?

“The Good Academic Research Practice is a consequence of our partnerships with the pharmaceutical industry in the late nineties, where they were already working according to the Good Clinical and Good Manufacturing Practice. At that time the Division of Pharmacology, professor Meindert Danhof and Oscar della Pasqua were about to start a collaboration with GSK (GlaxoSmithKline). GSK required that the data were produced according to GARP. With that requirement in mind, Della Pasqua had a look at all data filing within our department.

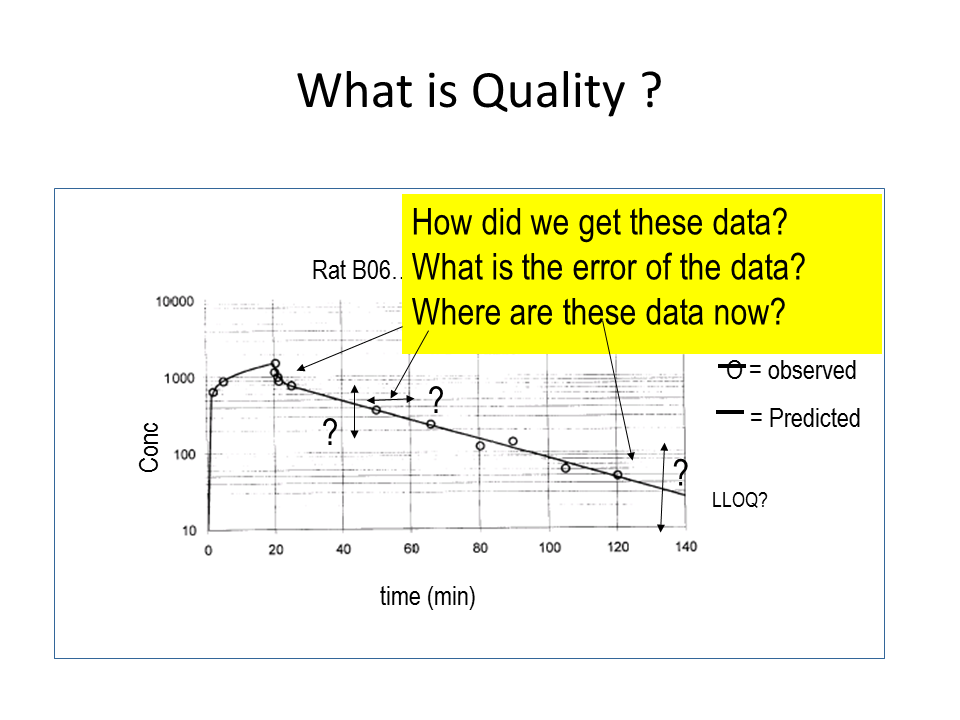

His investigation showed that I was the only one whose data were kept in a good way. It’s kind of in my DNA to organize everything neatly, and I had been working on this from the start of my PhD project. After Della Pasqua’s investigation, we started working with a file structure derived from the model GSK uses. This model focuses on three questions you should be able to answer about your data. How did we get these data? Where are these data now?”

Did this model meet with a lot of resistance?

“Not really, we all understood the necessity at the time. In hindsight we do see that the rules we made might not always have been clear enough though, or that individual researchers were not as compliant as they should have been. That is why some older files can still be hard to retrieve or interprete, even with individuals who were really keen on adhering to the GARP-model. To solve this problem, I put my hopes on the introduction of the electronic lab journal in academia. With those it is possible to enforce people to use a certain procedure. That way you will get an ‘iron discipline’.”

How do you ensure your researchers work conforms with GARP?

“In our Division everyone gets a GARP training, even master and bachelor students who work on a research project in our group. I think it is very important to start learning about data management early on in the education, preferably in the first year at university. Apart from the training we have a manager to oversee our data: Dirk-Jan van den Berg. I, myself, also look at it in a random way. And whenever someone sends me a file that is not GARP compliant, I will not comment on it before it has been adjusted. It takes, and will always take, quite a bit of effort and time to keep GARP up and running.

Overseeing the system has become less of a burden now data management is a part of the graduation trajectory for PhD’s. They will be evaluated by the promotion committee on these targets, which helps.”

Is enforcing truly necessary?

“It has its benefits. Take for example an Excel-sheet. How many ways are there to fill them out? What will you call the file, will you use multiple worksheets and what name will you give those sheets, will you include an explanation of the experiment in the first tab?

“It has its benefits. Take for example an Excel-sheet. How many ways are there to fill them out? What will you call the file, will you use multiple worksheets and what name will you give those sheets, will you include an explanation of the experiment in the first tab?

I gave a presentation on GARP at a meeting of the scientific council of the LACDR and several colleagues were really impressed, but others were not convinced that it could be used in their division as well. Some departments think you need to be able to use your intuition during experiments, and intuition is something you can’t always catch in organized structures. But actually you need to work in two phases. One rough system for preliminary research and a second, well-structured system for the methodologic experiments. In the end, all science is systematic.”

Will any type of research fit the GARP model?

“Our research usually consists of a wet part, the experimentation, and a dry part, the creation of computer models based upon the experimental data. It is easier for the wet part to adhere to GARP: you weigh something, do a calibration, repeat an experiment; it can all be described. In practice, it is much harder to make the development of computer models compliant. They are meant to fit as closely to the data as possible. If they do not fit the data, you try another model. This might look like an eyeball analysis, but even here we make objective choices on the basis of model quality parameters. The file name should describe the model structure, give objective information on the model quality and reflect on the choices why a model was chosen or rejected. It usually goes wrong in the phase where this last description has to be given. I keep pointing out this information is essential, even though our modelers regularly forget to add it.

In our Pirana software there is also functionality for model management, model execution, output generation and interpretation of results. But we need to comply to one overarcing approach.”

What did GARP give you in return?

“We created a mathematical model to predict the distribution of many types of medicines into the brain. The model is based upon a series of new experiments, but also on old experiments of which we had the well-defined data. Next we tried the model on other data sets of older experiments and used the fit to validate it. This has led to a nice generic brain distribution model that predicts the distribution of a medicine in the human brain on the basis of its plasma concentrations.”

Do you keep sharing data in mind when experimenting?

“We squeeze as much as possible out of our data and put this information in mathematical models for others to use. I sometimes see experiments done elsewhere that only look at the concentration of a compound at a certain time. That really is a waste, as you miss so much usable information then. We always measure concentrations and effects over time. In designing an experiment I always try to create data that is useful beyond the experiment. It saves experimental animals and time.”

What last piece of advice would you give to our readers?

“Do add GARP instructions to the bachelor courses as well. Explain them how to work with data and show them examples of well-structured files and garbage files in re-using data. Let them get stuck. It is this unpleasant experience that will motivate them later on to comply to good data-management.”

Dr. Liesbeth de Lange, interviewed by Drs. Rutger de Jong, science & data librarian Leiden, May 2016

In our course we use a handout on filenaming and folder structures which outlines the principles of the GARP standard file_naming_and_coding_GARP example_20151211

Presentation by Dr. de Lange on GARP: 20140312- GARP- LL- CODING_Projects_ Experiments_Files_Data

All images in this post courtesy of Dr. Liesbeth de Lange.