Descartes, social networks and popular culture: An excursion into digital scholarship

Thanks to an Elsevier Fellowship for Digital Scholarship, Paolo Rossini spent two months collaborating with members of the CDS. Using digital tools, he reconstructed the networks of René Descartes and his supporters from epistolary sources.

Guest author: Paolo Rossini, Digital Scholarship Fellow sponsored by Elsevier

René Descartes was a philosopher, mathematician and scientist. In fact, he was more than that – he was the father of modern philosophy and the inventor of analytic geometry. The Cartesian coordinate system and the Cartesian doubt – to mention two discoveries that bear Descartes’ name – are only a part of his legacy. Over the centuries, Descartes has grown to become a popular hero, joining the likes of Archimedes, Newton and Einstein. Bookstores abound with titles about his life, his works – even his skeleton. But how did Descartes build his reputation?

Unlike other intellectuals and artists, Descartes was not a misunderstood genius. On the contrary, his contemporaries soon acknowledged the disruptive power of his ideas. In the Netherlands, where Descartes spent most of his adult life, a new generation of university professors embraced his views and brought them into their classrooms. What is more, Descartes was, by the standards of the time, a best-selling author.

Figure 1: Descartes' house in Leiden.

There is no question that the main architect of Descartes’ reputation was Descartes himself. But isn’t it true that reputation is a matter of perception and should also be regarded as a collective phenomenon? In other words, how much are Descartes’ supporters responsible for his reputation, and how can we study this?

It is to answer these questions that I was awarded a Fellowship for Digital Scholarship sponsored by Elsevier. Thanks to this Fellowship, I had the possibility to collaborate with the Centre for Digital Scholarship at Leiden University Libraries. The Centre’s primary focus is to support scholars with data management, Open Access publishing and the integration of computational tools in their research. This was also my case. Inspired by such books as Malcom Gladwell’s The Tipping Point (2000), I had come to the conclusion that I could use network analysis to study how Descartes’ ideas spread out across Europe. Indeed, as Gladwell explains in his book, one of the keys to what he calls ‘social epidemics’ – when ideas and products become popular in an uncontrolled manner – is that they depend on the involvement of connectors. It’s easy to see how social networking platforms deeply affect the dissemination of new ideas in our society. But how did things work back in Descartes’ day?

As a matter of fact, Descartes was also a member of a quite extensive social network. It was called the ‘Republic of Letters’ and stretched all over Europe. In many respects, the Republic of Letters was not much different from today's Open Science movement. Indeed, just like Open Science, the Republic of Letters aimed to share knowledge across social, political and religious boundaries. As suggested by the name of their intellectual society, citizens of the Republic of Letters relied on correspondence to communicate information. They wrote letters to exchange opinions about recently published books, trade experimental observations and discuss the latest scientific discoveries. Luckily for us, tens of thousands of these letters, including more than 700 to and from Descartes, have been preserved, digitised and made available online. So for me the question was: how can I use this large amount of digital epistolary data to reconstruct Descartes’ network?

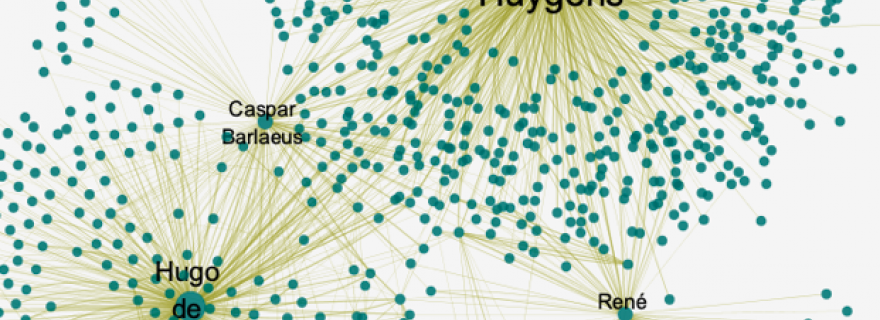

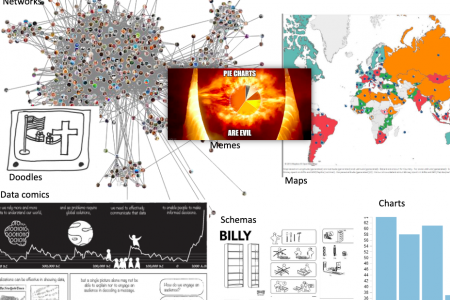

To put it simply, a network is a collection of nodes and edges. Nodes may represent people, while edges may represent connections between them. In the case of a correspondence network such as the Republic of Letters, connections are provided by letters exchanged between a sender and a recipient. So to digitally reconstruct the network of the Republic of Letters, we need at least three kinds of information: sender's name, recipient's name and a letter identifier. Technically, this information is called metadata, which means data about data. Historical documents in general, and early modern letters in particular, provide a lot of metadata: sender's name, recipient's name, origin, destination and date of the letters, just to mention a few examples. This metadata can be easily structured and converted into a digital format. Once this is done, we can use computers to process and study large quantities of metadata. This is what I did while I was a fellow at the Centre for Digital Scholarship. With the help of my great supervisors Peter Verhaar and Ben Companjen, I collected, curated and analysed metadata of some 13,000 letters [1]. All of this work allowed me to create this visualisation.

Figure 2: A network visualisation of the Republic of Letters created with the application Cytoscape. Green nodes represent people, while yellow edges represent correspondence between them. The size of the nodes is proportional to the number of correspondents.

Without going into too much detail, this visualisation shows a portion of the Republic of Letters represented as a social network. We can see that Descartes was part of this network. In fact, he was one of the most connected people in the entire network. In network terminology, people with a high number of connections such as Descartes are called ‘hubs’. Other examples of hubs in the Republic of Letters include Constantijn Huygens, Hugo de Groot and Caspar Barlaeus, three well-known figures of the Dutch Golden Age. Hubs are the reason why we often say that we live in a small world. Thanks to their high connectivity, hubs allow us to easily reach people that we would not otherwise know, or that might be too difficult to get in touch with. In short, hubs act as intermediaries, and in so doing they hold the network together.

From the above visualisation, we can gather that Descartes was quite a central figure in the Republic of Letters. This may begin to explain why and how he managed to spread his ideas so easily around Europe. However, at this point, I wondered if I could use digital tools to get a more complete picture of Descartes' network. As relevant as letters might be in the seventeenth century, they were neither the only nor the most important form of connection. Family, on the other hand, was the pillar on which early modern society was built. This is when Ben suggested to me: why don't you use Wikidata to reconstruct family networks? And so I did.

As you might already know, Wikidata contains structured information about items described in other Wikimedia projects, such as Wikipedia. So if Wikipedia informs us that Descartes' father was called Joachim, Wikidata gives us the same information, but in a structured way. As already explained, structured information is easy to extract and process using a computer, which is why Wikidata can be very useful when conducting digital research. Using the information retrieved from Wikidata, I managed to create this other visualisation of Descartes' network.

Figure 3: In this network visualisation, green nodes represent people, yellow edges represent correspondence, green edges represent family links. The size of the nodes is proportional to the combined number of epistolary and family relations.

As you can see, the network represented in this visualisation is considerably larger than that shown in Figure 2. In fact, we are talking about an increase in the number of nodes and edges of more than 50% (see Figure 4). But, numbers aside, what's important here is that, by taking family links into account, I added a further layer of complexity to the network visualisation. Indeed, we must not forget that network visualisations are models, and, as such, they run the risk of simplifying the reality they stand for. As a historian, I must be aware of this risk and take measures against it.

Figure 4: The increase in number of nodes and edges generated by the inclusion of family links.

To conclude, I hope to have given you an idea of what humanities scholars can accomplish by means of digital tools. As already stated, Ben, Peter and all the other team members of the Centre for Digital Scholarship were essential in collecting the data and creating the visualisations shown in this blog post. So if you are in Leiden and need assistance with your database or digitised texts, stop by the Centre; they will be more than willing to help. Finally, I cannot stress enough that the considerations presented here are not the final results of my research. If anything, they are the starting point.

Figure 5: Paolo Rossini working with Peter Verhaar and Ben Companjen in the Centre for Digital Scholarship.

[1] This dataset was provided by the ePistolarium, a web application developed at the Huygens Institute for the History of the Netherlands. The ePistolarium gives access to the metadata and full text of more than 20,000 letters exchanged mainly between Dutch correspondents during the seventeenth century. I am most grateful to the Huygens ING, and in particular to prof. Charles van den Heuvel, for allowing me to use the data of the ePistolarium in my research.